Glenda Stimpson

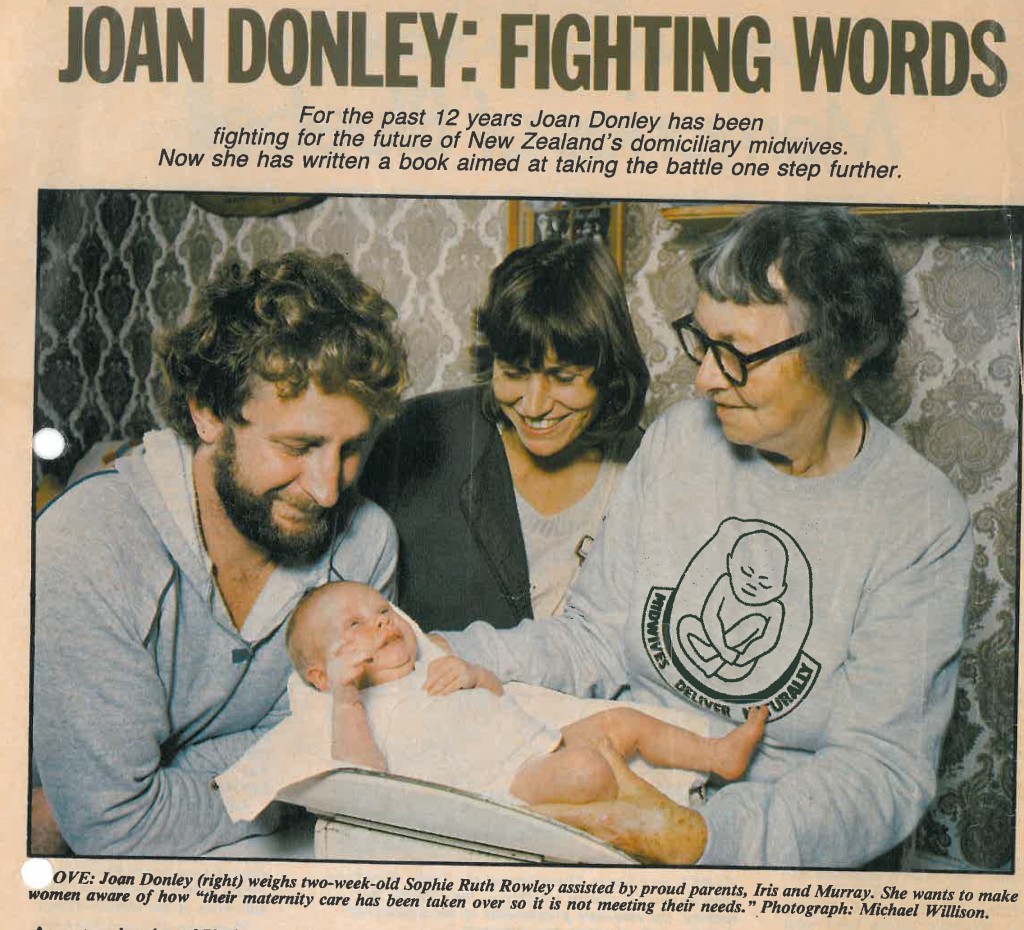

Glenda Stimpson, a well known Auckland midwife, practised as a Staff Midwife, Charge Midwife and relieving Afternoon Supervisor at National Women’s Hospital in Auckland, New Zealand, from 1966—2010. Glenda also filled the role of ‘unofficial historian’ for National Women’s Hospital tabulating key events, and the New Zealand College of Midwives photographing participants over the course of each NZCOM Conference. Significantly, Glenda was instrumental in ensuring that abandoned historical documents relating to National Women’s Hospital were included in the Papers of Joan Donley (1916-2005), 1933-2003. MSS & Archives 2007/15 held in the Special Collections at Auckland University Library.

Glenda recorded some background about the National Women’s Flying Squad, its process for accessing the service and some 48 ‘cases’ for which the Flying Squad was called between 22 October 1977 and 22 October 1977. Glenda notes that she began this document in 1971.

National Women’s Hospital Flying SquadFirst conceived of by Professor E. Farquhar-Murray in 1929, the organisation and use of the Obstertric Emergency Service was first established on a practical basis in Newcastle-on-Tyne in 1935. Since that time units have been developed in all parts of the world. Originally the aim of such a service was largely to render a woman temporarily fit to withstand the ambulance journey hospital. Of the first 27 women suffering from loss of blood and brought into hospital after restorative measure, 9 died in a state of shock. This frightful mortality was due principally to inadequate resuscitation to withstand travel. (No blood banks then.) This state-of-affairs led to the evolving of a highly skilled service including a senior obstetrician and a senior anaesthetist so that operative obstetrics was undertaken on the spot and in most cases the patient was never transferred to hospital. This principle is still adhered to in Newcastle-on-Tyne. With the greater availability of blood, more recently developed services have tended to aim at good resuscitation then transfer to a base hospital for further treatment. Although the Newcastle-on-Tyne Emergency Obstetric Service operates in a region where the domicilary confinement rate is still approximately 50%, it does not mean that we here in New Zealand with an almost 100% hospital delivery rate, can do without an emergency service – unless all women can be kept in hospital from ‘coitus to confinement’. In the last 20 years there has been a marked reduction in the number of neglected cases and mismanaged cases such as failed forceps or grossly exsanguinated women. But antenatal emergencies such as eclampsia, antepartum haemorrhage and haemorrhage from abortion still occur in the patient’s home and general practitioner units still require the services of prompt specialised assistance and access to blood, for urgent transfusion. Practical aims of an emergency service in New Zealand

Practical tips for the summoning practitioner

List of situations when Flying Squad should be summoned

Revised Flying Squad procedures

N.B. If you are not sending the Squad make certain who is responsible for calling the ambulance and ensure that a suitable escort for the patient will be provided.

NOTE If there is a delay or if you are in doubt as to whether the right message has been given ring Delivery Suite on the Direct Hot Line 686-581. NO calls can be transferred from this number. Flying Squad calls from 22/10/76–9/10/774/11/76 Papakura Hospital – Failure to Progress. Easy Keillands Rotation. Left at Papakura. 18/11/76 Waitakere Hospital – Retained Placenta. Manual Removal under General Anaesthetic. Left at Waitakere. 19/11/76 Papakura Hospital – Post Partum Haemorrhage Twenty minutes delay contacting flying squad. No change. Mother and baby transferred to National Women’s Hospital. 26/11/76 Papakura Hospital – Breech Delay 2nd stage. Patient delivered on arrival. Not transferred. 28/11/76 Papakura Hospital – ??Fit. Neurological examination normal. Transferred National Women’s Hospital. 3/12/76 Papakura Hospital Cord Prolapse. L.S.C.S at National Women’s Hospital. 9/12/76 Waitakere Hospital – Retained Placenta. General Anaesthetic, Manual Removal at Waitakere. Post Partum haemorrhage, 500 mls. Mother and baby transferred to National Women’s Hospital. 16/12/76 Bethany Hospital – Sev H.O.P 190/130 in Labour. Semi-Conscious – Hydrallazine. Transferred National Women’s Hospital. Forceps delivery. 18/12/76 North Shore Hospital – Post Partum Haemorrhage. 700 mls. No. I.V. in situ. Transferred National Women’s Hospital observation. 31/12/76 Papakura Hospital – Severe H.O.P in labour – 150/110 Sodi Gardinal, Valium, Pethidine. Transferred National Women’s Hospital. Forceps delivery. 2/1/77 North Shore Hospital – Post Partum Haemorrhage, 1.000 ml. BP. 120/80. Transferred National Women’s Hospital – observation. 7/1/77 Waitakere Hospital – Premature 26-27/40 R.M Transferred National Women’s Hospital. Berotec steroids. 7/1/77 Howick Hospital – Retained Placenta General Anaesthetic, Manual Removal at Howick. Left at Howick. 7/1/77 Papakura Hospital – Ante Partum Haemorrhage 32/40 No active bleeding. I.V Fluids – National Women’s Hospital. 9/1/77 Home- Ante Partum Haemorrhage. 18/40 aborted. ?1000 ml Blood. EUA, D&C Transfused. 9/1/77 North Shore Hospital HOP 150/100 Delivered. Valium, Hydrallazine. Transferred to National Women’s Hospital. 8/2/77 Papakura Hospital – Post Partum Haemorrhage B.P 70/30 ?700mls loss. Plasma, Hartmas. Transferred National Women’s Hospital. 12/2/77 Papakura Hospital – Ante Partum Haemorrhage 36/40. Normal Delivery at National Women’s Hospital. 17/2/77 Howick Hospital – Retained Placenta. General Anaesthetic, Manual Removal at Howick. Left at Howick. 18/2/77 Howick Hospital – ?Placenta Praevia – Breech. I.V Drip – Scan Xray – Normal Delivery at National Women’s Hospital. 19/2/77 North Shore Hospital – Server H.OP. B.P. 220/130 in Labour Hydrallazine Valium. Epidural Monitor Syntocinon. Forceps Delivery at National Women’s Hospital. 21/2/77 Waitakere Hospital – Retained Placenta. Placenta sitting in vagina. Removed. Remained Waitakere. 24/2/77 Waitakere Hospital – Avulsed Cord. General Anaesthetic. Manual Removal – adherent. Not transferred. 4/4/77 Pukekohe Hospital – Premature Labour 32-34/40 ion Labour. Berotec steroids. Breech Delivery National Women’s Hospital. 14/4/77 Warkworth Hospital – Failure to progress 2nd Stage. N.B lift out at Warkworth. Remained Warkworth. 15/4/77 Middlemore Hospital. Severe H.O.P 200/140 35/40 Hydrallazine. Transferred to National Women’s Hospital. ?outcome. 3/4/77 Middlemore hospital – 34/40 Fully Dilated. Steriods Berotec. Normal Delivery at National Women’s Hospital. 6/5/77 Auckland Hospital – Severe H.OP. 28/40, B.P. 220/120. Valium hydrallazine. Transferred National Women’s Hospital I.U.D. 10/5/77 Waitakere Hospital – Ante Partum Haemorrage. 36/40 R.M. Fetal Distress Delivery before arrival. Left at Waitakere Hospital. 14/5/77 Papakura Hospital – Retained Placenta. Manual Removal General Anaesthetic. Transferred National Women’s Hospital. Babe 11A. 18/5/77 Mater Hospital – Inverted Uterus – Gynae Operating Theatre. 18/5/77 Pukekohe Hospital – Patient Collapsed. ? Pulmonary Embolus. D.O.A at Pukekohe. P.M heart Failure. 5/6/77 Home of Compassion – Post Partum Haemorrhage ?700 ml. Patient Lifeless. B.P. OK 2o Plasma. Transferred National Women’s Hospital. 6/6/77 Papakura Hospital – Post Partum Haemorrhage. 1,000ml B.P OK. I.V. Drip. Syntocinon. Left at Papakura. 10/5/77 Howick Hospital – Post Partum Haemorrhage. 600 ml. EUA D & C at National Women’s Hospital. 7/7/77 Pukekohe Hospital – Post Partum haemorrhage 2,000ml 60/0. Plasma, Blood. General Anaesthetic. Transferred National Women’s Hospital. 10/7/77 Warkworth Hospital. Post Partum haemorrhage. 800mls + Blood Plasma. EUA at Warkworth pieces membrane removed. Left at Warkworth. 21/7/77 North Shore Hospital. Post Partum Haemorrhage 200 mls. B.P. 90/60 Blood, transferred National Women’s Hospital. EUA. 25/7/77 North Shore Hospital. H.O.P Abruption 32/40 IUD. Induced at National Women’s Hospital. Delivered. 28/7/77 Waitakere Hospital. Ante Partum haemorrhage 28/40 Minimal loss. Transferred National Women’s Hospital – Ward 5. 5/8/77 Warkworth Hospital. Ante Partum Haemorrhage. 800ml loss 42/40. Placenta Praevia. LSCS at National Women’s Hospital. 21/8/77 Papakura Hospital. Post Partum Haemorrhage. 1,00ml B.P. 80/60. Blood Plasma. General Anaesthetic. Placental tissue removed. Remained Papakura. 24/8/77 Waitakere Hospital – Retained Placenta. Placenta in vagina. Pethidine, Valium – Placenta removed. Remained at Waitakere. 25/8/77 Home Midwife – Retained Placenta. Blood loss 1,000ml. I.V Sytocinon. Transferred National Women’s Hospital. Manual Removal under General Anaesthetic. 3/9/77 Warkworth Hospital – Retained Placenta. General Anaesthetic. Removal. Blood loss 800mls. Patient remained at Warkworth. 10/9/77 North Shore Hospital – H.O.P Post Partum. 200/140. B.P on arrival 120/90. Transferred National Women’s Hospital – observation. 19/9/77 North Shore Hospital – Post Partum Eclampsia 140/95 (Twins). Paraldehyde, Valium. Transferred observation. 29/7/77 North Shore Hospital – Retained Placenta. Post Partum Haemorrhage. B.P 60/0. 2000 ml. Haemacel Blood Plasma. General Anaesthetic. Manual Removal. Transferred National Women’s Hospital. Observation. Paper written by G.E.Stimpson. Started 1971. |

The first of two deposits of secretarial archives from the Wellington Region of the College of Midwives is now online. You can access the archive from

The first of two deposits of secretarial archives from the Wellington Region of the College of Midwives is now online. You can access the archive from

“questions how the Western medical system handles childbirth: in Laing’s view, “one of the disaster areas of our culture.” Supported by arresting hospital footage and impassioned interviews with mothers, the film argues that women are often deliberately sidelined during the process of birth, and babies’ needs ignored. Screenings in the UK and US saw it contributing to a debate about newborn care; one that remains ongoing. Birth won a Feltex award for best documentary. Read the

“questions how the Western medical system handles childbirth: in Laing’s view, “one of the disaster areas of our culture.” Supported by arresting hospital footage and impassioned interviews with mothers, the film argues that women are often deliberately sidelined during the process of birth, and babies’ needs ignored. Screenings in the UK and US saw it contributing to a debate about newborn care; one that remains ongoing. Birth won a Feltex award for best documentary. Read the